WHAT WE WERE

What was climbing like in the 1970s? What was it like to stand at the base of a big wall in the Dolomites and conceive a new route? It was like reinventing the good old days, before the dark period in which conquest by any means (the Golden Age of aid climbing) became the only method of progress. We searched for new lines that would go free and were possible using removable protection—no bolts. Style was our most important criterion, not the grade.

The less gear one used the better. Respecting our predecessors and impressing insiders—our peers—were more important than seeking the recognition of the general public. It was meaningless to achieve higher grades at the expense of style.

Using the same prerequisites as our predecessors, we sought to evolve; following even stricter ethics became the clearest and most honest answer.

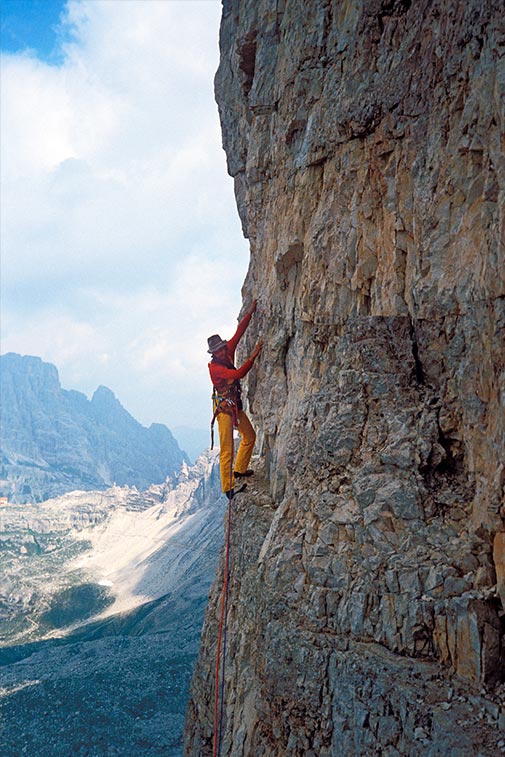

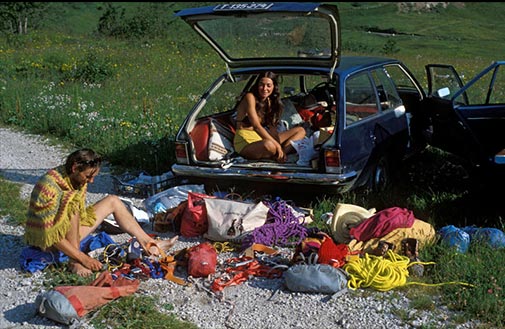

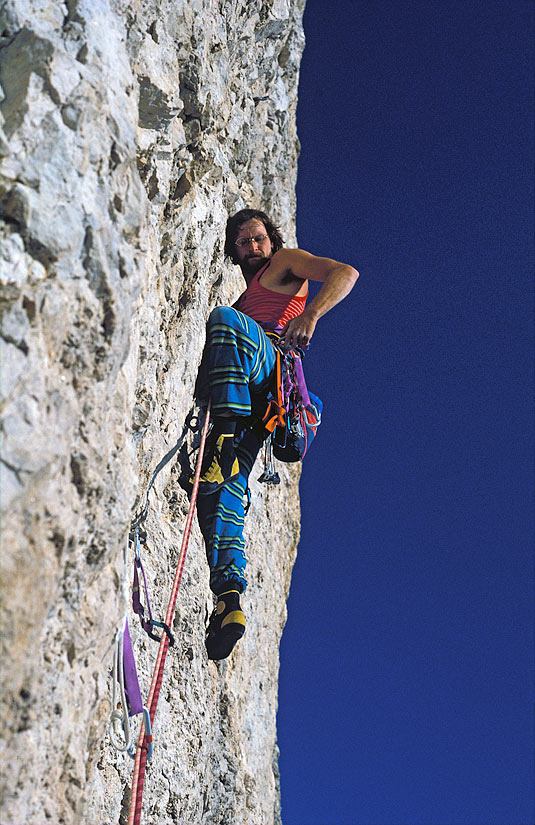

Our climbing world in the Seventies: We would consider our options from the base of the wall and then start climbing free, following the rock’s features like edges, pockets, flakes, and cracks. It was also key that we find natural placements for protection. A rack of nuts and Hexentrics, some pitons—that was it. Dealing with risk was the central problem around which everything else evolved. Climbing free into the unknown, one faces a situation that is radically different from that encountered on an established sport route. Pushing the grades under these conditions required both boldness and creativity. Sometimes we were lucky to survive, but that didn’t make us any less easygoing. Our lifestyle and spirit hove closer to hippie culture than to the pathetic “hero image” of mainstream alpinism.

WHAT WE Became...

The end of adventure means the end of freedom

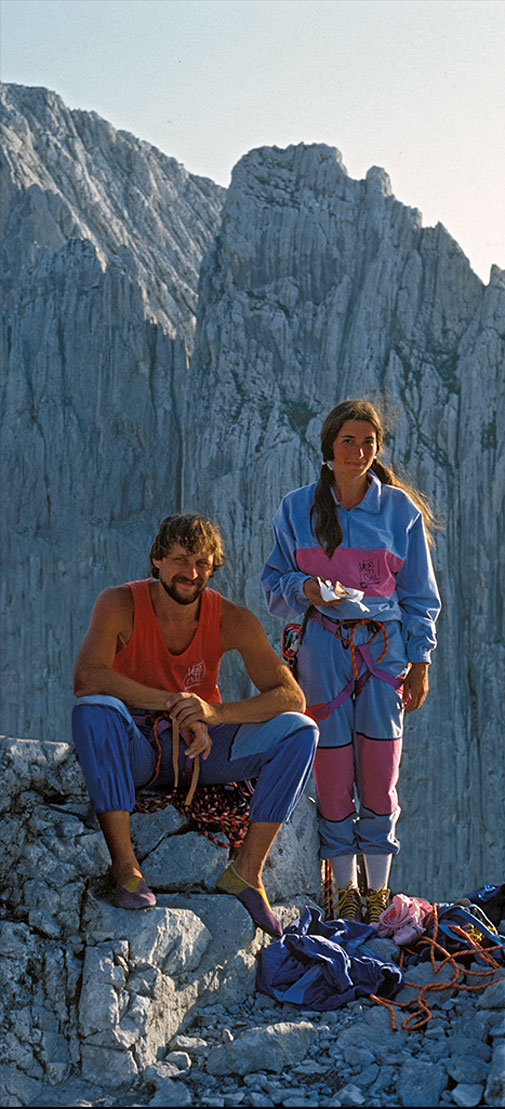

In the early 1980s sport climbing garnered its first public attention. There was something new and fresh in the air. Free climbing finally became clearly defined (the concept of the “redpoint”), and the whole game took on a new dimension. Despite a clear shift toward a more gymnastic and sport-oriented ethos, nobody thought that the era of risk and adventure would end. Approaching a wall from the base and exploring it in clean free-climbing style was still the highest goal of the mountain climber—of course, without the use of bolts. That’s why redpoint ascents of classic aid routes became the new trend for grade chasers. Most of these routes already had in situ protection: old pitons or in some cases bolts, a prerequisite for hard sport climbing. But what had happened to our dream world, to our “separate reality,” to our nonconformist lifestyle? We never imagined that the mountains would become a sporting arena! Climbing was fascinating to us, because it was different from everyday life and common sports. Climbing was exclusively our world, and we enjoyed the freedom to play our own personal game, far from the spotlight.

1982 - freeing aid routes on the Rotwand, Dolomites

When Nico Mailänder published an article about Pete Livesey’s efforts to free some of the classic Dolomite aid routes, we were all impressed. Livesey’s efforts sparked my own curiosity, and for the first time I started to work out: traverses on the stone walls of our house, pull-ups, slack lining. A redpoint ascent of the Buhl route on the Rotwand became my first sport-climbing experience in the Dolomites. It was interesting, but didn’t change my opinion that the real evolution would take place on first ascents, without any in situ protection.

I had always considered sport climbing and mountain climbing to be two different games. Sport climbing is sport; mountain climbing is adventure. Sport climbing is free of risk; mountain climbing is characterized by risk. Sport climbing is a purely athletic pursuit, while the difficulty of a mountain route is mainly determined by the psychological challenge.

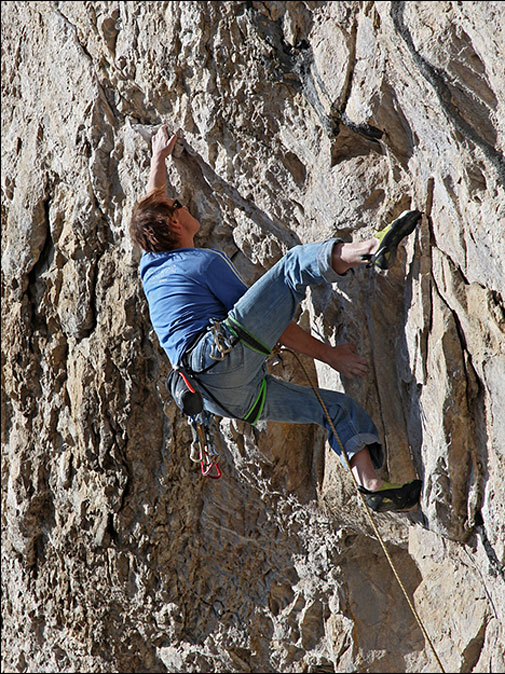

Today’s reality: many mountain routes are prepared like sport routes. That means exploring from protection point to protection point in a mixed style that blends free and aid. Redpoint attempts follow only after the climber has perfectly prepared and protected the route. This preinspection sometimes involves fixing ropes from the top down, working single moves, and placing protection on toprope.

For me, such climbs are “sport climbing of the uncomfortable sort” and have nothing in common with the adventure climbing of our predecessors nor with the style-conscious minimalism of my generation. Nevertheless, these climbs get written up, publicized as evolutionary high points and the new standard in mountain climbing. Nobody seems to question this development. It strongly recalls the dark ages of the “Direttissimas,” when conquering the impossible by any means was a means to capture the interest of the general public, and obtain honor and even medals from the authorities. Strangely enough, today’s mindset is still mired in the era of the 1936 Eiger tragedy and other heroic suffer-stories. The only difference is that today’s “heroes” represent their sponsors instead of nationalistic interests, as they did in the pre-WWII era.

In this new business-driven model of alpinism, even dedicated risk-deniers are considered heroes—as soon as they connect their name to a mountain. The good old atmosphere of mountain drama still confers spectacular cachet, adding value to otherwise unremarkable performances.

Fact is: today’s generation simply ignored our generation’s purist mindset and has pushed evolution according to their own rules, virtually through the back door.